Essay on Freud and Surrealism

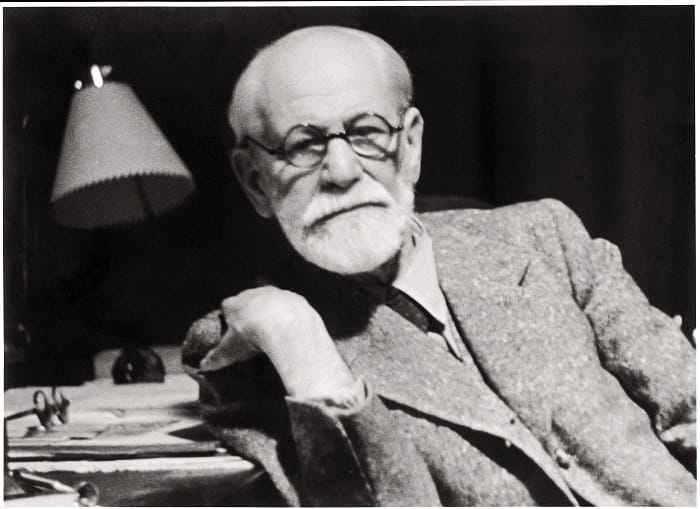

Dr. Sigmund Freud takes a special place among the psychologists of the 20th century: his works have radically changed the look of contemporary psychology, covered the issues of individual’s inner organization, one’s motives and feelings, conflicts between personal desires and needs to follow public morality, as well as showed the ephemeral nature of individual’s understanding of oneself as a person and the vision of others. As a psychological doctrine, Freudism was aimed at studying the hidden links and foundations of individual’s psychic life basing on the idea of suppression of the whole set of pathological representations (including sexual ones) beyond consciousness and repressing them in the unconscious. The ideas of Viennese psychologist and philosopher couldn’t help having special meaning to the representatives of the Surrealist circle, who sought to introduce Surrealism not as a new aesthetic approach to art, but as a new way of seeing the world: their aim was to reconcile an individual with one’s own subconscious mind first, and then with the outside world as a whole. However, it would be simplistic to think that the surrealists worked under Freud’s prescription or illustrated his ideas. Deeply influenced by the psychoanalytic discoveries of Freud, Surrealism rather was assisted in the formation of invaluable techniques of separation from reality and methods of indulging into the twilight world of instincts and intuition.

Freudianist methodology in the art of 1920’s-1930’s

Deeply psychological prism of surrealism, its expression of unconscious fantasies, sexual fears and complexes, the transfer of childhood and personal life experiences to the language of allegory – these internal aspects were considered to be determining quality of Surrealism at its dawn in the 1920-30’s. Back in 1924, André Breton, the founder of the Surrealist movement, wrote that the Manifesto of Surrealism basically links roots, aspirations, inner freedom, and creative courage of the new movement with the discoveries of Freud. Indeed, Freudianism provided Surrealism with the brilliant conceptual basis and grounded validation of its ideas, thus filling the key messages of emerging art trends with sophisticated meaning (Eagle 31-55).

In particular, the Surrealists could not help but notice that the “incidental” techniques of early Surrealism and the chaotic Dada movement, such as exquisite corpse, frottage, or dripping (i.e. arbitrary spraying of paint on canvas, fully complied with the Freudian method of free associations used in the study of individual’s inner world. Later, when the principle of illusionist photographing of the unconscious was asserted in the art of Dali, Magritte, Tanguy, and Delvaux, it was impossible not to recall that psychoanalysis developed a technique of documentary reconstruction of dreams (Durozoi 53-57). Interconnections and similarities were significant, especially considering the fact that psychoanalysis paid utmost attention on the same states of mind that the Surrealists were primarily interested in (dreams, visionary, mental health, child mentality, and psyche of primitive type, i.e., the one that is free from restrictions and prohibitions established by the civilization), and thus, we have to admit the initial parallelism of interests, perspectives, methods and conclusions between Freudianism and Surrealism.

Furthermore, following the logic of Freud’s philosophy and the flow of subconscious ideas, the Surrealists put themselves outside the art as a form of reflection over the reality. Thus, in Max Ernst paintings Ubu Imperator (1923) and The Hat Makes the Man (1920), the dry and lifeless imagery shows the illogical combination of people and things. Later, in his Natural History series (1925), Ernst used Surrealist automatist technique where he gave meanings to the random lines arising out of the frottage by finding their similarities with the scenery, fantastic birds and plants, destruction from earthquakes and other natural phenomena. The artist then argued that during the process of creating these collotypes he tried to bring himself to the state of hallucination to imagine order inside chaos. Another influential representative of Dada movement, Francis Picabia used this approach in his early Surrealist works Broderie (1922) and Sunrise (1924). These and other works are obviously a glimpse into the confused and anarchic rebellion of artists against boring and at the same time necessary and inevitable reality, and eventually, against the entire human past and present. On this basis, the notion of the pure nature of the creative unconscious was shaped. The understanding of Surrealism thus receives its groundings in the belief of a higher reality of certain forms previously not taken into account, such as associations manifested in dreams or in the free play of thought, etc. (Wintle 167-73)

Eventually, Surrealist artists started to pay paramount attention to the Freudian method of dreams analysis, by which a painting was written or sketched immediately after waking up, before recent hallucinations and subliminal images were affected by comprehension, real consciousness. In particular, this method was widely applied by Salvador Dali, who, clearly imitating psychoanalysis and even competing with it, ended up with creating a paranoid-critical method, according to which originally pure images could be placed in the context of chaotic unconscious impulses (Auster 74-75). For instance, his The Birth of Liquid Fears (1932), Nostalgia of the Cannibal (1932) and Atavism at Twilight (1934), as well as many others, obviously conceal the real world from the world, which can be considered ideal. Similarly to the logic of dreams, most often Surrealist paintings reveal either personal desires or secret fears: bleeding ulcers, loss of viscera, faces corroded with cancer, hungry ants, hermaphrodites feeding on excrement, etc. All of whose metaphors they are clearly the symbols of anxiety; the deformation of forms, like in The Persistence of Memory (1931), expresses the reality of pain, death, inhibition, and suppression of desires which destroys life like death itself does. At yet, as Dali puts it, the painting appeared due to the associations he had when looking at Camembert cheese melting in the sun ( Durozoi 117-124).

Another typical example of creating Surrealist works can serve a painting Person Throwing a Stone at a Bird (1926) by Joan Miro, which by artist’s own admission, was painted under the influence of hallucinations caused by hunger. In his turn, Yves Tanguy set himself the task of creating works based on childishly naive worldview. Translating abstract metaphysical concepts by means of painting, he created The Furniture of Time (1939) on a regular blue-gray background, revealing the emptiness of alien landscapes and the helplessness of the small figures through depicting abstract shapes and inadequate forms (Paglia 122-127). In whole, Surrealism becomes committed to the destruction of all other psychic mechanisms, aiming to replace them in the process of resolving any existing fundamental problems of life.

Moreover, the adoption of the Freudian position on the absence of fundamental differences between the healthy and the mentally ill led to the recognition of insanity condition as the most favorable to the Surrealist art, as soon as this condition cannot be controlled by reason. Defining of art as a form of insanity, the subject of art – as purely personal complexes, and its content – as imagery not related to the real world, but rather based on repressed personal aspirations and fantasies, has finally resulted in the denial of the social role of art (Wintle 93-94). Using the analogy drawn by Freud between dreams and art, Surrealist artists were factually putting themselves outside art as a form of reflection of reality.

Conclusion

As a prominent psychiatrist of early 20th century, Freud created the theoretical ground for the emergence of Surrealism, while surrealist artists found sources of inspiration in his theory and attempted to free their subconscious through illogical, surrealistic imagery. Following Freud’s explanations of human nature, Surrealists understood their art as psychic automatism in its true state, the real process of thought on seeing the world. In other words, being a record of thought in the absence of control from the mind and beyond any aesthetic and moral considerations, a work of art could express the direct flow of associations emerging in the unconscious. In this perspective, the unconscious was recognized as the only absolute meaning, life with all its peculiar laws that had emerged long before there were fundamental concepts of good and evil, God and reason. The development of Freudianism served as an additional argument that the significance of the subconscious should not be underestimated or considered as something minor. Due to Freud’s theory of psychoanalysis, Surrealism had the opportunity to insist that it is not a groundless fantasy fiction and the movement of anarchists from art, but a new word in the understanding of man, art, history and thought. Having obtained a solid ideological support, Surrealism further prevailed and largely influenced art around the world up to the mid-20th century, successfully applying such Freudian ideas as the logic of dreams, the denial of separation of ugliness and beauty, good and evil, sublimation of desires, etc. At the same time, these ideas put Surrealists into the opposition to the social role of art, developing a revolutionary and unique form of art without rules.

Do you like this essay?

Our writers can write a paper like this for you!