Eugene Delacroix the first ethnographic essay

The Orient has been a central attraction to both the Western artists during the nineteenth century, and in this period a number of Oriental tales and pictures help shaped ideas of the East and feeds into stereotypical perceptions of the Orient lands; particularly Turkey, Eygypt, Syria and more recently North Africa. These works of art not only help us to understand how prominent artists interpreted the orient of his dream, but also points to popular changing perceptions, conflicts and how art can contribute to the way in which we perceive the Orient during that era. A number of artist are prey to received idea of the Orient as lawless, barbaric and backward by engaging and reproducing such political orientalist thoughts into their works. Many of these works continue to be particularly relevant today, when a range of challenges and current debates continuously challenge the ways in which we think about, and come to terms with, the Orient.

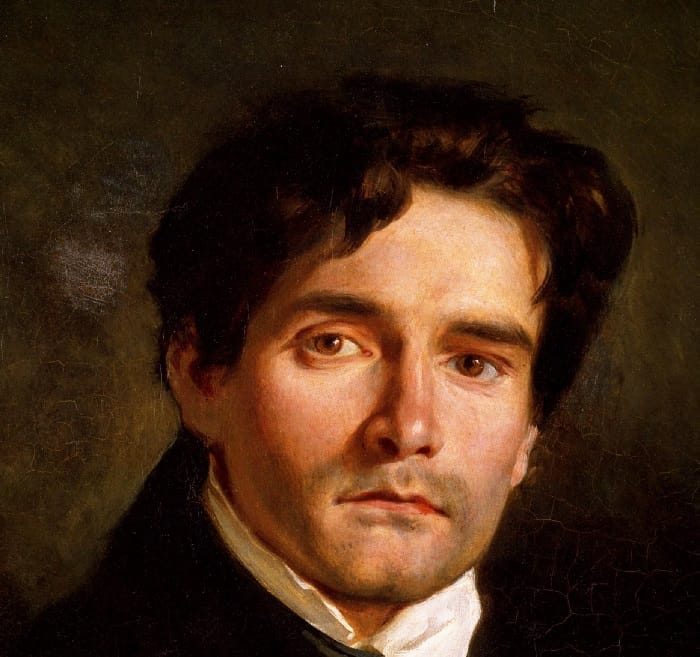

Of these various challenges, this essay will in particular focus on the issue of contradiction and ambiguities surrounding Eugene Delacroix (1798-1863) as an ethnographer during his voyage to North Africa, in 1832.Being relatively new to the country’s social, political and geographic structure, Delacroix struggled with ‘coming to terms’ with the reality that was before him. In order to explore the possibility of Delacroix being the first ethnographer to have traversed through North Africa, this essay will draw on Delacroix’s watercolour sketches; A courtyard in Tangier; Arab woman sitting on some cushions, study for the Women in Algiers; Arab fantasia in front of The gates of Meknes. This essay will also analyse Delacroix’s oil paintings; Jewish Wedding; Women of Algiers In their Apartment; Moroccans conducting Military Exercises (Fantasia). All these paintings have a connection to Delacroix journey and through the comparative analysis between these paintings, a wealth of notes can be drawn from, learnt and interpreted.

Firstly, this essay will provide a brief overview of Delacroix’s pre-North Africa conception of the oriental scene in order to contextualise the significance of his later construction of Oriental art. Secondly, the essay will draw from his watercolour sketches in order to consider how he grappled with being confronted by the aesthetic spectacles of North Africa and demonstrate how Delacroix’s direct relationship with the Orient space may or may not have transformed his vision and approach of the Orient. Thirdly, this essay will contrast Delacroix’s watercolour sketches with that of his major canvases, and consider elements that perhaps could justify Delacroix’s transformation from the orientalist artist to the ethnographic one. Prior to North Africa, Delacroix had been a proponent of the Romantic whose skill set in George P. Mras[1] view involves subject matters that are exotic and whose aim in structuring composition is to heighten emotional response and drama, with the use of the artist’s personal interpretation and imagination. Hence, Delacroix approach to Orient themes then, was filled with violence and cruelty in the oriental subjects. Death of Sardanapulas (1826), for example, influenced from Lord Byron’s 1821 tragedy Sardanapulus[3], incorporated these romanticised elements. The tone to the tragedy was elevated with the addition of more dead bodies and murders than the original scene, the reds and yellows in this image intensified the scene and made it more disorderly to the eye.The clever use of lighting draws our eyes towards the moment of disorder at the center of the picture, illuminating the atmosphere of death and destruction. The artist deliberate enhancement to the original imagery only stressed strong degree of pain, suffering and tortures which highlights the barbaric nature of the Orient. Such paintings are classic examples of artworks which explicitly served the political interest in Orientalist art that fed the nature of orientalist thoughts of the period.

The Death of Sardanapalus (1827) is the early paining created several years before his trip to North Africa. The Death of Sardanapalus contains strong orientalist trends which, to a certain extent are similar to those depicted in his Saada, the Wife of Abraham Benchimol, and Preciada, One of Their Daughters (1832). The Death of Sardanapalus focuses on the depiction of the last days of the ancient king Sardanapalus, who decided to kill his wives, servants and himself to escape from enemies, who were about to capture his city[4]. However, European trends are stronger in this painting compared to the watercolor painting created during his trip to North Africa. For instance, the female nudity was traditional for European art of that time.

Delacroix’s freedom of visual expression evident in his watercolour sketches (1832) affected perceptions of the stereotypical Orientalist thoughts in a very different, perhaps more subtle, way than his earlier works. It also mark a departure from his previous intense styles. Perhaps this freedom was due to his effort to preserve the fleeting experience that may be lost if not instantaneously captured[5], and at the same time revealing imageries, techniques and aesthetic discourse that are fresh. Whats remarkable about Delacroix’s sketches is that despite the hasten showcased a discipline that is conservative and pure in its content. Brahim Alaoui[6] concludes that Delacroix’s ability to capture shed his pre conceived notion of the Orient, and freed himself of former prejudices and had approached Morocco with a fresher, newer outlook.

This can seen in watercolour sketches created by Delacroix, including A courtyard in Tangier; Arab woman sitting on some cushions, study for the Women in Algiers; Arab fantasia in front of The gates of Meknes. These sketches are light hearted attempts to record the authentic environment of Arabs.

He paints with great vividness and emotion but with the minimal use of bright colours. Such superficial but detailed sketches resemble the documentation, archiving and note taking, collecting details and architecture of those communities, which Delacroix attended during his trip to North Africa. His trip brought him new impressions and bright emotions uncovering the truth about the life of local tribes and people inhabiting Arab countries and Maghreb region.

However, in accordance with Brahim Alaoui’s description, Elizabeth Fraser argues that

On the one hand, we have Edward Said and Linda Nochlin arguing that European culturally-embedded stereotypes about North Africa were reproduced in artistic and cultural production, regardless of what artists encountered.

Through the myriad of studies in watercolour of various subjects of the everyday was amassed during his journey, it is showcases Delacroix versatility in capturing

and these were later mixed and match used much later, in his major canvases. Watercolour studies like Arab Interior and A courtyard in Tangier are examples of an ethnographic documentation of the living conditions of the people in Morocco and such sketches are used in his major canvases, years down the road. Both sites display an airy, spacious room painted with a thin layer of paint that emphasised the light feel of the site. Delacroix has employed exceptional skill and care in authentically reproducing intricate detail of the architectural structure (anathema to his usual painterly practice), this painting is designed to communicate the inherent cultural differences of the East. Details from A courtyard in Tangier was also later used as the main scene for his oil painting The Jewish Wedding (1837/41).

Apart from Delacroix’s fascination with the architectures in North Africa, he was also interested in the human and social areas and this is seen in his watercolours Arab fantasia in front of The gates of Meknes and the study for the Women in Algiers. Delacroix recorded those activities in his sketch to show the lifestyle of Arabs which was different from the traditional lifestyle of Europeans. More important, it was different from the lifestyle of Arabs imagined by Orientalists. Another sketch, Arab Interior shows the interior architecture and design of traditional Arab households. Delacroix makes the sketch but records distinct details that help viewers to understand the atmosphere of the interior of Arab households and the lifestyle of people. Light walls decorated with some paintings, places to seat located close to the window, the arch above the seats, densely decorated window and other elements convey the original atmosphere of Arab household. Even thought this watercolour is just a sketch but still it conveys details that allow viewers to understand main elements of the décor and interior of Arab buildings and households. Delacroix’s sketch is the view from within the building.

Arab woman sitting on some cushions; Study for The Women of Algiers is another watercolour sketch that also shows the interior of Arab household but, unlike Arab Interior, Arab woman sitting on some cushions; Study for The Women of Algiers depicts a woman lying on cushions. Her posture is absolutely natural, lazy in a way, and apparently relaxed. She is not confused at all. There are no signs of anxiety on her face, but her eyes are looking a bit downward that may be the implication of some embarrassment from uncovering her private life to a stranger, like Delacroix. Nevertheless, she is not over-agitated. She leans on her elbow casually that shows that she has accustomed to such position and it is absolutely natural for her. The interior surrounding the woman is relatively simple. She lies on cushions which cover a large part of the room around her. There are no many elements of furniture, which was traditional for European interior, which Delacroix accustomed to. However, the interior depicted on Arab woman sitting on some cushions; Study for The Women of Algiers seems to be intentionally simple to show that the Arab woman is not pursuing some extraordinary comfortable conditions. The minimalism of the furniture is absolutely natural since the woman seems to have everything she needs and she is not even looking for more being satisfied with her life.

In Arab fantasia in front of The gates of Meknes record in rapid and literal way what he actually observed. Arab fantasia in front of The gates of Meknes shows Arabs conducting military exercises which were probably their traditional activities. This stirring scene – a tumultuous line of violent, turbaned Arabs charging towards some hidden enemy – had as its source a fantasia viewed by Delacroix while in Morocco: a choreographed military spectacle that is unique to Morocco, whose origin was, as its name suggests, more in the imagination than actuality. The painter’s fluid and gestural brushwork, the sharp contours and the rich palette, produce an image of the Orient as dazzling and theatrical, a wild place of dust and violence.

After his trip to North Africa, the artist attempted to convey the authentic spirit and way of life of North Africa which was quite different from the one he used to. At this point, his earlier works, like The Death of Sardanapalus (1827), are absolutely different from his post-trip works. The Death of Sardanapalus is vulnerable to the considerable influence of Orientalism, whereas Arab fantasia in front of The gates of Meknes reflects the authentic way of life of the population of North Africa. In such a way, the artist attempted to show the real life and the different way of life of the local population to make Europeans acquainted with the totally different culture. At the same time, he debunked those Orientalist myths concerning North Africa that prevailed in European culture before his trip to the region.

Delacroix preserved in his attempt to make sketchlike technique as an expressive device – a visual stimulus intended to activate the viewer’s imagination into creative response.[7] However, his oil canvases have a stronger impact on the audience due to the use of richer colours and concise brush moves, especially in the center of his paintings, such as Women of Algiers In their Apartment, where the artist depicts females in details. His brush moves are accurate and mirror the certainty of the painter in every move he made. This oil canvas depicts vividly the interior of the female part of Arab household. Again the author depicts the same cushions, minimalistic interior with a few elements of furniture and cushions on the carpet covering the floor of the room. Women sitting on the carpet and cushions or leaning on them talk to each other but there are no males around them. this details is important because Delacroix shows local traditions of segregation of male and female parts of households. By the way, the same trend can be traced in Delacroix’s Jewish Wedding oil on canvas created in 1837. The artist depicts the Jewish wedding, which he probably witnessed during his trip to North Africa. The distinct feature of this painting is the presence of males only with a woman dancing in the left part of the painting. This painting basically supports the male/female segregation in North African communities. Hence, the author shows distinct features of the traditional lifestyle, rites, architecture, interior and decorations of households of people living in North Africa. Delacroix pays attention to details of clothing, relations between people, and their lifestyle.

Thus, Delacroix became the first ethnographic artist, who recorded the life of people in North Africa, their lifestyle, habits, clothing, entertainments, architecture, interior, gender relations and many other issues. Canvases and sketches mentioned above show the development and evolution of Delacroix. Sketches and canvases discussed above show the evolution of Delacroix from the artist influenced by European Orientalism to the ethnographic artist, who first made sketches to record important details of the life of people living in North Africa, while later oil canvases created after his return from Africa complete the transformation of his views and show that Delacroix became the first ethnographic artist revealing the different way of life of North African people compared to the traditional way of life of Europeans.

[1] Sheriff, M.D. (2010). Cultural Contact and the Making of European Art since the Age of Exploration. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press

[2] http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/euor/hd_euor.htm

[3] http://www.artble.com/artists/eugene_delacroix/paintings/the_death_of_sardanapalus

[4] Delacroix, E. (1827). The Death of Sardanapalus. Available online from http://www.artble.com/imgs/e/7/a/934950/the_death_of_sardanapalus.jpg

[5] Sheriff, M.D. (2010). Cultural Contact and the Making of European Art since the Age of Exploration. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press

[6] Ibid.

[7] Pg 79 eugene delacroix’s theory of art by George P. Mras, Princeston, New Jersey, Princeton university Press, 1966, published for the department of art and archeology

Do you like this essay?

Our writers can write a paper like this for you!